Equine Acute Laminitis

Nicola Menzies-Gow MA VetMB PhD DipECEIM CertEM(Int.med) FHEA MRCVS - 09/08/2016

Equine Acute Laminitis

Introduction

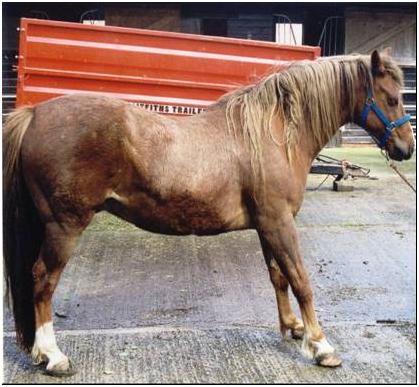

Laminitis is characterised by failure of the attachment of the epidermal cells of the epidermal (insensitive) laminae to the underlying basement membrane of the dermal (sensitive) laminae.  It can arise in association with diseases characterised by sepsis and systemic inflammation such as gastrointestinal disease, pneumonia and septic metritis, endocrine disorders including pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID, Equine Cushing’s disease) and equine metabolic syndrome (EMS), and mechanical overload (supporting limb laminitis). However, in the UK, it is most commonly associated with access to pasture. Certain individual animals appear predisposed to recurrent pasture-associated laminitis, but the exact mechanisms underlying their predisposition remains unclear. It seems likely that there are certain phenotypic traits common to these individuals. Multiple variables have been evaluated as risk factors for laminitis with the findings generally being inconsistent between studies. An association between the occurrence of laminitis and being a pony, the spring and summer months, being female, increased age and obesity have been demonstrated in some studies. In addition the endocrinological disorders PPID and EMS may play a role in this predisposition.

It can arise in association with diseases characterised by sepsis and systemic inflammation such as gastrointestinal disease, pneumonia and septic metritis, endocrine disorders including pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID, Equine Cushing’s disease) and equine metabolic syndrome (EMS), and mechanical overload (supporting limb laminitis). However, in the UK, it is most commonly associated with access to pasture. Certain individual animals appear predisposed to recurrent pasture-associated laminitis, but the exact mechanisms underlying their predisposition remains unclear. It seems likely that there are certain phenotypic traits common to these individuals. Multiple variables have been evaluated as risk factors for laminitis with the findings generally being inconsistent between studies. An association between the occurrence of laminitis and being a pony, the spring and summer months, being female, increased age and obesity have been demonstrated in some studies. In addition the endocrinological disorders PPID and EMS may play a role in this predisposition.

Pathogenesis

Acute laminitis can be divided into three stages. Firstly, there is a developmental or prodromal phase that begins with contact with the pathophysiological trigger and ends with the onset of lameness up to 72 hours later. This is followed by the acute phase during which the clinical signs are seen. Thus, the clinical signs only become apparent once the lamellar tissues have already been subjected to activation of inflammatory, metabolic and degenerative changes. The acute phase is followed by either resolution of the disease or the chronic phase. There is evidence to support a role for inflammation, extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, metabolic disease and endothelial and vascular dysfunction in the pathogenesis of laminitis. However the exact cascade of events and the interactions between all of these processes is yet to be elucidated. (Belknap JK, Moore JN, editors. Special issue: inflammatory aspects of equine laminitis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2009;(T3–4):149–262)

- Inflammation

Although the role of inflammation in laminitis has been questioned because of the minimal neutrophil infiltration present histologically, recent research has produced abundant evidence of inflammatory changes during laminitis. Although the mechanisms linking consumption of pasture with development of lamellar inflammation have not been fully elucidated, it is thought that a systemic inflammatory response that accompanies hindgut carbohydrate overload somehow initiates lamellar inflammatory events. - ECM Degradation

The extracellular matrix is a diverse structure formed of structural proteins, proteoglycans, regulatory proteins, proteases, and protease inhibitors that are responsible for the maintenance of structural support, movement, growth, remodelling and healing, along with the modulation of cytokines, inflammation and cell migration. Previously it was thought that dysregulation of the protease enyzymes known as matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) was fundamental to laminitis. More recent research has shown that whilst MMP activation does occur, it is not an initiating event. It now seems that laminar separation may occur following a failure of epithelial adhesion molecules (ie, hemidesmosomes), which attach the epidermal cells to the basement membrane. Dysregulation of cell adhesion is most likely caused by inflammatory and/or hypoxic cellular injury. - Metabolic Disease

Laminitis can affect any horse, but is more common in ponies, and certain individual animals appear predisposed to the development of recurrent pasture-associated laminitis. The two most likely endocrinological disorders that may play a role in this predisposition are those conditions associated with excess glucocorticoids, namely PPID and those associated with insulin resistance (IR), namely EMS. Animals at greatest risk of pasture-associated laminitis have a metabolic phenotype including obesity and IR, similar to that seen in human metabolic syndrome (HMS). Thus the same pathologic mechanisms that underlie the cardiovascular disease associated with HMS, including changes in insulin signalling, inflammatory cytokines and endothelial dysfunction caused by adipose tissue-derived mediators could contribute to laminitis. Evidence shows that summer pasture appears to produce metabolic responses in laminitis prone ponies leading to the expression of this at-risk metabolic phenotype, including IR, hypertension (suggestive of endothelial dysfunction) and dyslipidaemia. Further studies have demonstrated a strong, positive relationship between pasture non structural carbohydrate (NSC) content and circulating insulin concentrations; increased carbohydrate consumption exacerbates IR in horses; and feeding a fructan-type carbohydrate produces an exaggerated insulin response in laminitis prone ponies. Thus, it may be exacerbation of IR by increased carbohydrate consumption that results in laminitis in certain individuals during the spring and summer months.

The two most likely endocrinological disorders that may play a role in this predisposition are those conditions associated with excess glucocorticoids, namely PPID and those associated with insulin resistance (IR), namely EMS. Animals at greatest risk of pasture-associated laminitis have a metabolic phenotype including obesity and IR, similar to that seen in human metabolic syndrome (HMS). Thus the same pathologic mechanisms that underlie the cardiovascular disease associated with HMS, including changes in insulin signalling, inflammatory cytokines and endothelial dysfunction caused by adipose tissue-derived mediators could contribute to laminitis. Evidence shows that summer pasture appears to produce metabolic responses in laminitis prone ponies leading to the expression of this at-risk metabolic phenotype, including IR, hypertension (suggestive of endothelial dysfunction) and dyslipidaemia. Further studies have demonstrated a strong, positive relationship between pasture non structural carbohydrate (NSC) content and circulating insulin concentrations; increased carbohydrate consumption exacerbates IR in horses; and feeding a fructan-type carbohydrate produces an exaggerated insulin response in laminitis prone ponies. Thus, it may be exacerbation of IR by increased carbohydrate consumption that results in laminitis in certain individuals during the spring and summer months.

However, it must be remembered that not all laminitis prone animals are IR and/or obese and not all IR animals are laminitis prone. Thus it remains unclear whether IR per se plays a direct role in the development of laminitis, or whether other factors associated with IR increase susceptibility to laminitis when the animal is exposed to conditions known to trigger development of the condition such as carbohydrate overload during grazing.

- Endothelial and Vascular Dysfunction

Vascular events which have been identified in the early stages of laminitis include digital venoconstriction and consequent laminar oedema. This venoconstriction may be caused by platelet activation and platelet-neutrophil activation resulting in the release of the vasosctive mediator serotonin (5-HT). In addition, normally the gastrointestinal flora produces relatively high concentrations of various dietary amines by fermenting ingested amino acids, which remain within the gastrointestinal lumen. Grass contains soluble carbohydrate in the form of fructans, a polysaccharide that is not digested by the small intestines and passes through to the hindgut. Fermentation of large amounts of carbohydrate by the hindgut bacteria is associated with increased numbers of certain Gram positive bacteria that produce increased amounts of these vasoactive dietary amines which may enter the circulation and directly and indirectly contribute to digital venoconstriction. Finally, IR in other species alters endothelial function creating a pro-inflammatory condition, leading to platelet and leucocyte activation, increased production of the potent vasoconstrictor endothelin-1 and production of mediators of inflammation and oxidant stress. Thus, alterations in digital vascular haemodynamics associated with inflammation, platelet activation, and the action of vasoactive amines absorbed from the intestinal tract may contribute to lamellar injury.

Diagnosis

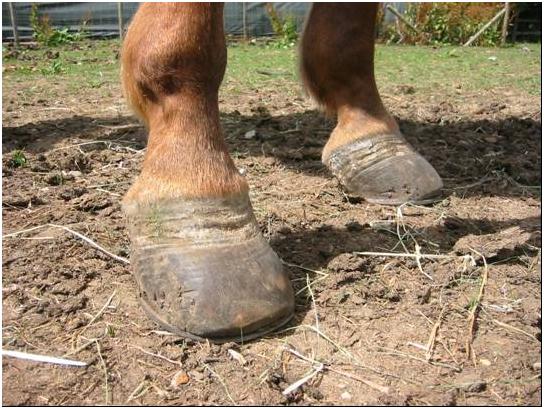

The diagnosis of laminitis is usually based on the clinical signs which include lameness affecting two or more limbs,  characteristic stance of leaning back on the heels and taking weight off toes, bounding digital pulses, increased hoof wall temperature, pain on hoof tester pressure at the region of the point of the frog and possibly a palpable depression at the coronary band. The lameness can vary in severity from that only perceptible at the trot through to spending prolonged periods recumbent. The severity of the laminitis can be classified in many ways, but the commonest is to use the Obel grading system.

characteristic stance of leaning back on the heels and taking weight off toes, bounding digital pulses, increased hoof wall temperature, pain on hoof tester pressure at the region of the point of the frog and possibly a palpable depression at the coronary band. The lameness can vary in severity from that only perceptible at the trot through to spending prolonged periods recumbent. The severity of the laminitis can be classified in many ways, but the commonest is to use the Obel grading system.

Further tests are performed in those cases where an underlying endocrinological abnormality is suspected such as PPID or EMS and radiographs are taken in those cases where movement of the pedal bone is suspected.

Treatment

Acute laminitis is a medical emergency and treatment should be initiated as soon as possible after the onset of the clinical signs. By the time the clinical signs become apparent, the lamellar tissues have already been subjected to activation of metabolic and degenerative changes. Thus, therapy should be aimed at providing analgesia and foot support. The use of therapies to alter digital perfusion remains controversial.

- Analgesia... non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) given either orally or intravenously are the first choice for analgesia as they also inhibit part of the inflammatory cascade. There is no evidence to suggest that any one specific NSAID is superior to the next. If they do not provide sufficient pain relief, then opiates can additionally be used such as butorphanol, pethidine, morphine, fentanyl patches.

- Foot Support... supporting the foot is an essential part of the management of acute laminitis. The horse naturally adopts a stance that bears most of the weight over the caudal part of the foot rather than the painful toe region.

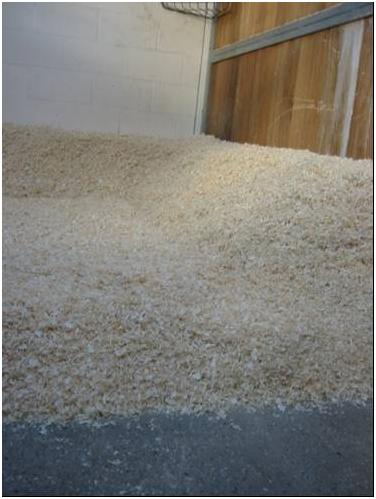

Additional support should be supplied to this region of the foot in order to provide pain relief and minimise the mechanical forces on the laminae and hence laminar tearing and pedal bone movement. The simplest method is to increase the depth of the bedding and ensure that the bedding extends to the door. Shavings, sand, peat or hemp based products are best as they pack beneath the feet better than straw or paper. Extra support can be applied directly to the caudal two thirds of the foot itself. This can be done in a variety of ways that can be broadly divided into frog only supports and combined frog and sole supports.

Additional support should be supplied to this region of the foot in order to provide pain relief and minimise the mechanical forces on the laminae and hence laminar tearing and pedal bone movement. The simplest method is to increase the depth of the bedding and ensure that the bedding extends to the door. Shavings, sand, peat or hemp based products are best as they pack beneath the feet better than straw or paper. Extra support can be applied directly to the caudal two thirds of the foot itself. This can be done in a variety of ways that can be broadly divided into frog only supports and combined frog and sole supports.  Frog only support can be achieved using rolled up bandaging material of the same length as the frog, placed along the length of the frog and secured in place with adhesive tape. Alternatively, a commercially available product such as the lily pad or TLC frog support can be used. Combined frog and sole support can be provided using for example dental impression material that is moulded to the contours of the caudal two thirds of the foot or Styrofoam pads that are crushed by the weight of the horse.

Frog only support can be achieved using rolled up bandaging material of the same length as the frog, placed along the length of the frog and secured in place with adhesive tape. Alternatively, a commercially available product such as the lily pad or TLC frog support can be used. Combined frog and sole support can be provided using for example dental impression material that is moulded to the contours of the caudal two thirds of the foot or Styrofoam pads that are crushed by the weight of the horse.  There is no evidence to suggest that any one foot support method is superior.

There is no evidence to suggest that any one foot support method is superior.

Regardless of which type of support is used, they must be removed intermittently and the feet examined for evidence of softening and thinning of the sole over the toe region suggestive of imminent pedal bone penetration and for evidence of infections such as thrush or white line infection that require additional treatment. The supports should be left in place whilst the horse remains acutely painful. They can be replaced by more permanent alternatives such as heart bar shoes, egg bar shoes or imprint shoes that can be combined with gel or dental impression material sole supports once the horse is comfortable if required.

They can be replaced by more permanent alternatives such as heart bar shoes, egg bar shoes or imprint shoes that can be combined with gel or dental impression material sole supports once the horse is comfortable if required. - Vasodilator or Vasoconstrictor Therapy... the use of vasodilator or vasoconstrictor therapy in the treatment of laminitis remains controversial due to lack of knowledge of the pathophysiology of the disease. Vasodilator therapy is frequently used once the clinical signs have become apparent based on laminitis being a consequence of digital hypoperfusion. Acepromazine is the most effective digital vasodilator available. However, it should be acknowledged that even if the pathophysiology of laminitis involves vasoconstriction, this has normally resolved once the clinical signs become apparent. Nevertheless, the sedative effect of acepromazine may have the additional beneficial effect of reducing movement or even resulting in increased periods of time spent recumbent with the weight taken off the feet.

Cryotherapy has been shown to prevent experimentally-induced laminitis and it was postulated that this was due to prevention of vasodilation. However, cryotherapy will also protect against ischaemia by reducing cellular metabolic demands and inflammation by decreasing enzymatic activity. Regardless of the mechanism of action, continuous adequate and controlled chilling of the digits over a prolonged period of time would be difficult to achieve in the clinical situation. - Additional Therapies... additional therapies are indicated if an underlying endocrinological disorder is diagnosed. The treatment options for PPID include the dopamine agonist pergolide (Prascend, Boehringer) which is licensed for the treatment of PPID in the horse and reported to be effect if up to 85% cases; the serotonin antagonist cyproheptadine (Periactin, Merk Sharp & Dohme Ltd) which is reported to be effective in up to 60% cases; and the cortisol antagonist trilostane (Vetoryl, Dechra) which is reported to be effective in 70% cases but will only alter the clinical signs associated with excess cortisol.

The treatment of EMS should focus on management changes aimed at weight reduction (see prevention) to reduce adipose mass and so decrease mediator production and exercise which reduces IR and inflammation. If these are unsuccessful alone, then pharmacologic interventions can be additionally used in the short term (3-6 months). The only drug that has been used to date in the UK to improve insulin sensitivity in EMS is metformin. However evidence suggests that only a very small amount (7%) of the drug is absorbed orally and that it may not have insulin sensitising effects.

Prevention

Prevention of pasture-associated laminitis centres on achieving and maintaining an optimum body condition and on limiting intake of pasture NSC (non-structural carbohydrate). A diet based on grass hay (or hay substitute) with low (<10%) NSC content should be fed and cereals avoided. Soaking hay in water for 16 hours before feeding will leach water soluble carbohydrates, however this does not reliably decrease the NSC content to <10% in every case and ideally forage should be analysed. If weight loss is required hay or hay substitute should initially be provided at <1.5% of current body weight per day, with subsequent further reductions in feed amount depending on the extent of weight loss. It is preferable not to decrease forage provision to less than 1.0% of target body weight as this may increase the risk for hindgut dysfunction, stereotypical behaviours, ingestion of bedding, or coprophagy. The forage should be divided into three to four feeds per day and strategies to prolong feed intake time should be considered, such as use of haynets with multiple small holes. This diet low in NSC also has the additional benefit of improving insulin sensitivity in IR animals.

A diet based on grass hay (or hay substitute) with low (<10%) NSC content should be fed and cereals avoided. Soaking hay in water for 16 hours before feeding will leach water soluble carbohydrates, however this does not reliably decrease the NSC content to <10% in every case and ideally forage should be analysed. If weight loss is required hay or hay substitute should initially be provided at <1.5% of current body weight per day, with subsequent further reductions in feed amount depending on the extent of weight loss. It is preferable not to decrease forage provision to less than 1.0% of target body weight as this may increase the risk for hindgut dysfunction, stereotypical behaviours, ingestion of bedding, or coprophagy. The forage should be divided into three to four feeds per day and strategies to prolong feed intake time should be considered, such as use of haynets with multiple small holes. This diet low in NSC also has the additional benefit of improving insulin sensitivity in IR animals.

The NSC content of pasture fluctuates widely. It decreases when the plant is growing as it is using up the NSC to provide energy for growth, and increases when the plant is not growing but continues to photosynthesise e.g. when there is high light intensity, low temperatures, lack of water. In addition, the NSC content is also affected by season. It is low in early spring, but increases in late spring. Thus, zero grazing should be considered. However, if a laminitis prone animal is to be turned out, steps should be taken to minimise NSC intake...

The NSC content of pasture fluctuates widely. It decreases when the plant is growing as it is using up the NSC to provide energy for growth, and increases when the plant is not growing but continues to photosynthesise e.g. when there is high light intensity, low temperatures, lack of water. In addition, the NSC content is also affected by season. It is low in early spring, but increases in late spring. Thus, zero grazing should be considered. However, if a laminitis prone animal is to be turned out, steps should be taken to minimise NSC intake...

- The pasture should be managed to encourage growth, but it should be regularly topped.

- Animals should be turned out from late night to early morning when the NSC content of the pasture is lowest.

- Grazing should be particularly limited in spring and autumn when the grass is growing.

- Turn out should be avoided if there has been a frost with bright sunshine or a drought as this is restrict growth but photosynthesis will continue allowing the NSC to accumulate.

- Paddocks should be rotated in order to keep them at the ideal height. If the grass is too short, it will be stressed and have a higher NSC content, if the grass is too long although the NSC content of each plant will be lower there will be a greater amount available for consumption.

- Methods to restrict intake such as strip grazing and grazing muzzles should be considered.

It must be remembered that forage-only diets do not provide adequate protein, minerals, or vitamins and so a low-calorie commercial ration balancer product that contains sources of high-quality protein and a mixture of vitamins and minerals to balance the low vitamin E, vitamin, copper, zinc, selenium, and other minerals typically found in mature grass hays is therefore recommended. If weight gain is required or the animal is undertaking a large amount of exercise, then a forage-based diet may not meet energy requirements and caloric intake can be increased by adding unmolassed soaked sugar beet pulp to the diet at 0.2-0.7kg/day or by feeding vegetable oil (100-225ml SID or BID up to a maximum of 100 ml/100 kg of body weight).

Several supplements containing magnesium, chromium or cinnamon are marketed with claims for improved insulin sensitivity but scientific evidence of their efficacy is lacking

Exercise is also essential in the prevention of laminitis as it has been shown to reduce IR, suppress inflammation and decrease food intake. It would appear that light exercise is sufficient to improve insulin sensitivity, but that this probably needs to be maintained on a regular and possibly even daily basis for the improvement to persist. Obviously this will only be possible once an animal has recovered from an episode of laminitis and is sound and there should be a gradual increase in the intensity and duration of the exercise undertaken.

This article was kindly sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, makers of Prascend, the licensed treatment for clinical signs associated with Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID):

This article was first published on VetGrad.co.uk in 2012.